Towards a Social Practice of Imperial Life

To this day, empires seem to be everywhere. Scholars argue that the continuity of empire is due to its ubiquity, since empires covered most of the world, and due to its performativity, since most people in the world “lived” imperial routines even beyond the formal end of empire. At the same time, historians have revealed that empires allowed more participation than hitherto assumed. To be sure, empires restricted the political participation of the imperial “subjects,” but these were far from being passive. Even inhabitants whom empires deprived of their essential rights shaped imperial life through their social practices, daily routines, and subtle resistances. Applying a praxeological approach to the history of empires, this blogpost explores the complex preconditions for voluntary participation and its unintended results in the light of imperial constraint.

Participation in imperial projects can only partially be understood by measuring the political power of pro-imperial and anti-colonial ideologists. Most inhabitants of empires lived their everyday lives without explicitly taking sides, no matter if they were subaltern or privileged. The analysis of their social practices can explain how voluntary participation shaped the routines of empires without presenting a simplistic picture of a clash between empire builders and enemies of empire. Intuitively, one might assume that voluntary participation is less likely to occur in empires than in nation states, which give their citizens rights and privileges in exchange for material and ideological loyalty. However, voluntary participation also shaped empires. This participation needs explanation, which can be found in the practice of everyday life rather than in ideal-type theories of imperialism and anti-imperialism.

Voluntariness and its Unintended Effects: The Man Without Qualities

Even before praxeology had become a fully-fledged theory, those who reflected on voluntariness in empires almost naturally chose a praxeological approach. One striking example is Robert Musil, who described everyday life in the Habsburg Empire on the brink of World War I in his book The Man Without Qualities. Musil’s protagonist“without qualities”is an average inhabitant of a (continental) empire. He declares himself a defender of the Habsburg Empire and voluntarily starts a campaign to celebrate its grandeur. His actions and the behavior of his compatriots, however, actually lead the Habsburg Empire into World War I and provoke its collapse. Writing between 1930 and 1943, Musil was well aware that voluntary imperialist fervor might have effects opposite to those desired, unintentionally laying the foundations for imperial disaster.

Throughout the book, Musil describes voluntariness as highly ambiguous and barely distinguishable from either the force of circumstance or the collective behavior that caused the collapse of imperial society. He uses the neologism “voluntaryinvoluntary” (p. 1686) and gives his reflections on voluntariness in empires a more general significance: “In ordinary life we act not according to motivation but according to necessity, in a concatenation of cause and effect; of course, something of ourselves is always involved in this concatenation, which makes us think we are free. This freedom of will is man’s ability to do voluntarily what he wishes involuntarily. […] It cannot be divided according to the opposition between freedom and compulsion: it is the highest freedom and the most profound compulsion” (p. 1686). As Musil zooms in on the analysis of “ordinary life” practices, he notes that “something of ourselves” makes people act. This “something of ourselves” does not amount to an unrestrained free will, he warns, since free will is imagined rather than real. Voluntarism is thus ambiguous, since people only do voluntarily what they want involuntarily. By using the idea of voluntariness rather than voluntarism to describe people’s actions, Musil can make a more nuanced argument and show that a pure “free will” is little more than an idealistic self-description of the protagonists we analyze. Further, with regard to motivations, he denies the explanatory power of binary oppositions such as individual freedom vs. external constraint. His insight that motivations were based on “deepest constraint and highest freedom” reveals that in practice freedom and force seem to be less of a contradiction than we might assume.

Thilo Fehmel has suggested that the Man Without Qualities was praxeological avant la lettre, since Musil adopted elements of Kurt Lewin’s social-psychological field theory. Inspired by explanatory models developed by physics, Lewin traced action and behavior back to an interactive and relational field of powers. According to Lewin, power relations in such fields are dynamic and their boundaries fluid. Subjects are equally objects of specific and situative constellations in the field. The fields themselves are invisible but manifest themselves through their effects.

Ambiguities of Voluntariness in Colonial Empires

Lewin’s field theory is undoubtedly reminiscent of Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of the same name, which became one of the pillars of his theory of practice. It is no coincidence that Bourdieu developed his praxeological approach in an imperial context, when facing everyday life in French Algeria and adopting anthropological methods to describe it. In Algeria, Bourdieu also sharpened his notion of habitus, which he then applied to European societies. He traced habitus back to repeated and routinized everyday practices, which produce and reproduce social distinctions. In his later work, he also reflected on voluntariness as a marker of social distinctions, for example when he recalled “a social psychology experiment which showed that the same act, that of giving blood, is seen as voluntary or forced depending on whether it is performed by members of the privileged classes or the working classes” (Bourdieu 1986, p. 178). This structuration of society through certain patterns of behavior was also true of imperial and post-imperial settings, in which racist distinctions were implemented in everyday practice through language, behavior, segregative routines, and discriminatory habits.

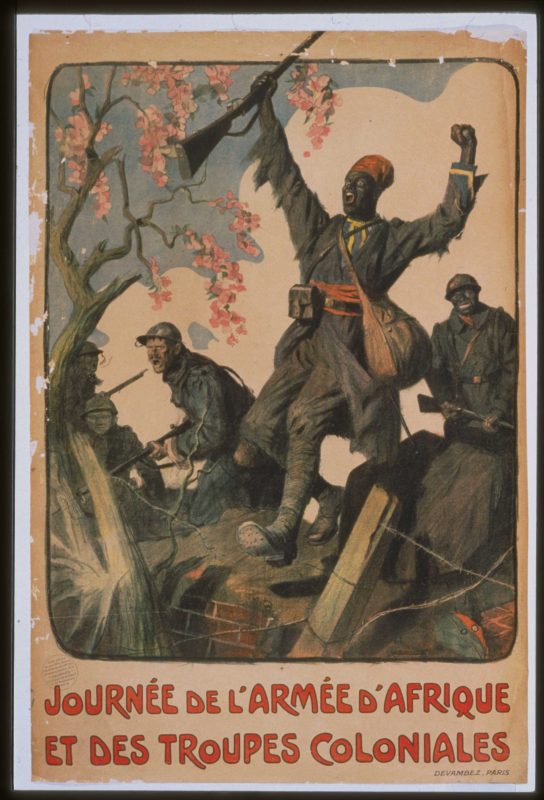

Praxeological approaches to empires fell on fertile ground among historical anthropologists such as Georges Balandier, who famously described the ambiguities of the “colonial situation” (1951). Frederick Cooper has recently revived Balandier’s “colonial situation” and with it the praxeological approach to voluntary participation in (colonial) empires. According to Balandier, the encounter between colonizers and colonized did not bring about a sharper distinction between the two groups but new interactive patterns of behavior. These might be key to understanding these subalterns’ voluntary participation in imperial projects, although they continued to be victims of its structural discrimination. Their voluntary participation as soldiers, workers, and administrators cannot be seen as a simple approval of empire but was a complex set of behaviors that might even destabilize the enforced imperial system. Quite a few Africans who joined the French army to fight in World War I, for example, did so voluntarily. Some voluntarily paid this so-called “blood tax” to avoid disreputable forced recruitment, while others hoped that voluntarily displaying their loyalty might enhance their social and political position within the empire. Whatever the reasons for joining the army, the voluntariness of their participation gave them the legitimacy to request more rights and political recognition after the war. When recognition failed to materialize, the volunteers turned against the empire that had deceived and disappointed them. Even defenders of the empire acknowledged the legitimacy of their rebellion.

As in Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, voluntary participation was imposed by the colonial situation and could have effects opposite to those initially intended by protagonists. A praxeological approach to empires can thus illustrate the complex convergence of voluntariness and coercion inherent in many societies. Furthermore, it reveals how a practice of voluntariness, for example when donating blood or paying the imperial “blood tax,” structured and restructured societies. Hence, curiously, voluntary participation could simultaneously perpetuate imperial structures and threaten the formal existence of empires.

Suggested Citation: Wagner, Florian: “Doing Voluntariness in Empires: Towards a Social Practice of Imperial Life”, Voluntariness: History – Society – Theory, November 2021, https://www.voluntariness.org/doing-voluntariness-in-empires/