Committing to Civic Education Voluntarily: A Res Publica in a Liberal U.S. Democracy

The Struggle for Democracy

The figures presented in the 2023 Freedom House report continue to show democratic backsliding worldwide. Since the end of the Cold War, democracies have been dying due to the failings of their own elected governments. In 2016, political scientists Yascha Mounk and Roberto Stefan Foa already referred to “The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Disconnect,” in which, rather than dying overnight, democracies slowly wither away if not nourished by the active participation and trust of their citizens. Their sample showed that citizens in North America and Western Europe are less satisfied with their governments and are open to other forms of governance. According to Mounk and Foa (2016) we are experiencing a decline in regime legitimacy, not merely government legitimacy. The figures on trust in democracy correlate with age and in the U.S. not even 30 percent of those aged 40 and below consider it essential to live in a democracy, compared to 70 percent of the cohort born before World War II (see Civics 101, 2023). You cannot sustain a democracy if people have no wish to live in one.

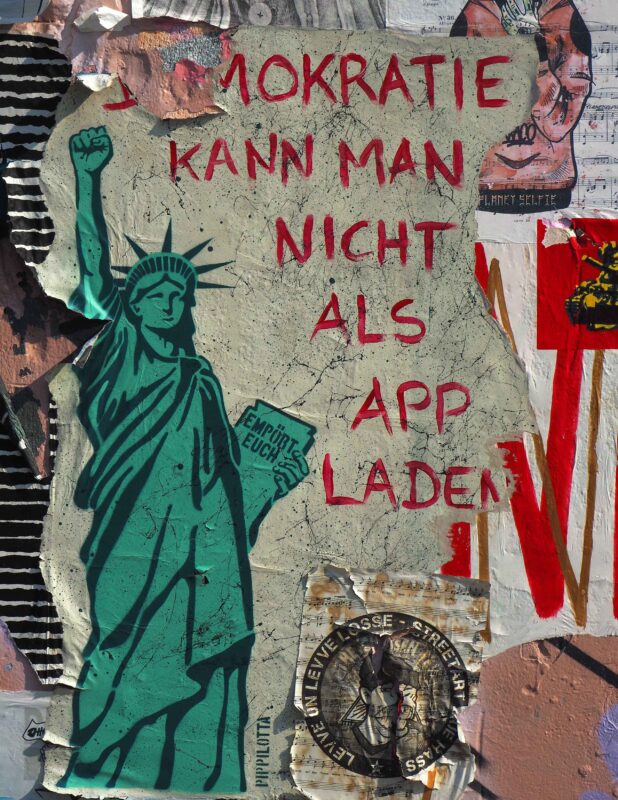

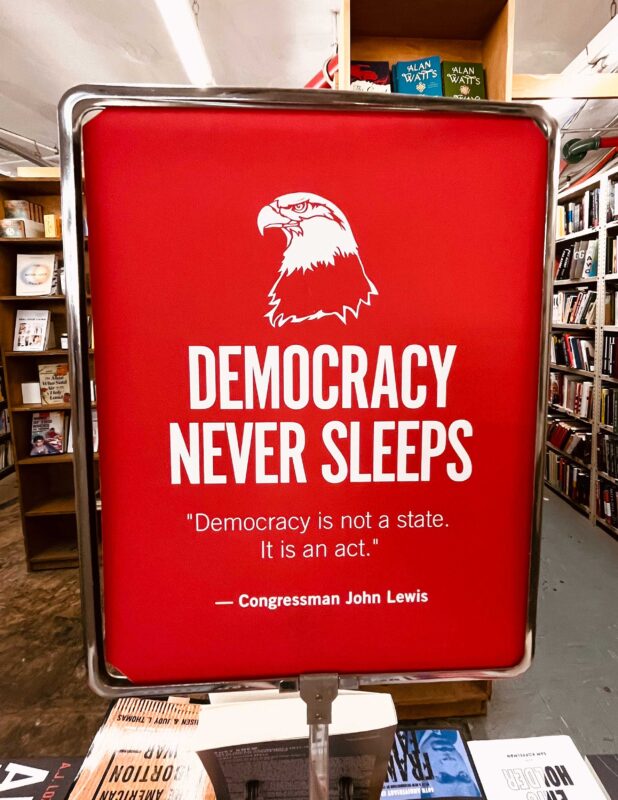

History is replete with democracies’ struggles and fight for survival. Even the American Founders were unsure if their experiment would endure. Benjamin Franklin famously referred to “A republic if you can keep it”, while John Adams wrote that “[d]emocracy never lasts long. It soon wastes exhausts and murders itself. There never was a Democracy yet, that did not commit suicide.” Even President Barack Obama warned in his farewell address that “[o]ur democracy is threatened whenever we take it for granted.” If we want to keep living in democratic systems and hopefully even better-functioning ones, it is our responsibility as citizens to step up and voluntarily participate in them. The Constitution is “just a piece of parchment. It has no power on its own. We, the people, give it power.” Democracy needs its citizens to exercise their rights as well as duties and to actively, voluntarily participate in it, “[n]ot just when there’s an election, not just when your own narrow interest is at stake, but over the full span of a lifetime.” Thus, self-government is one of the most crucial practices in a liberal democracy.

Self-Government and Civics: Matters of Voluntariness

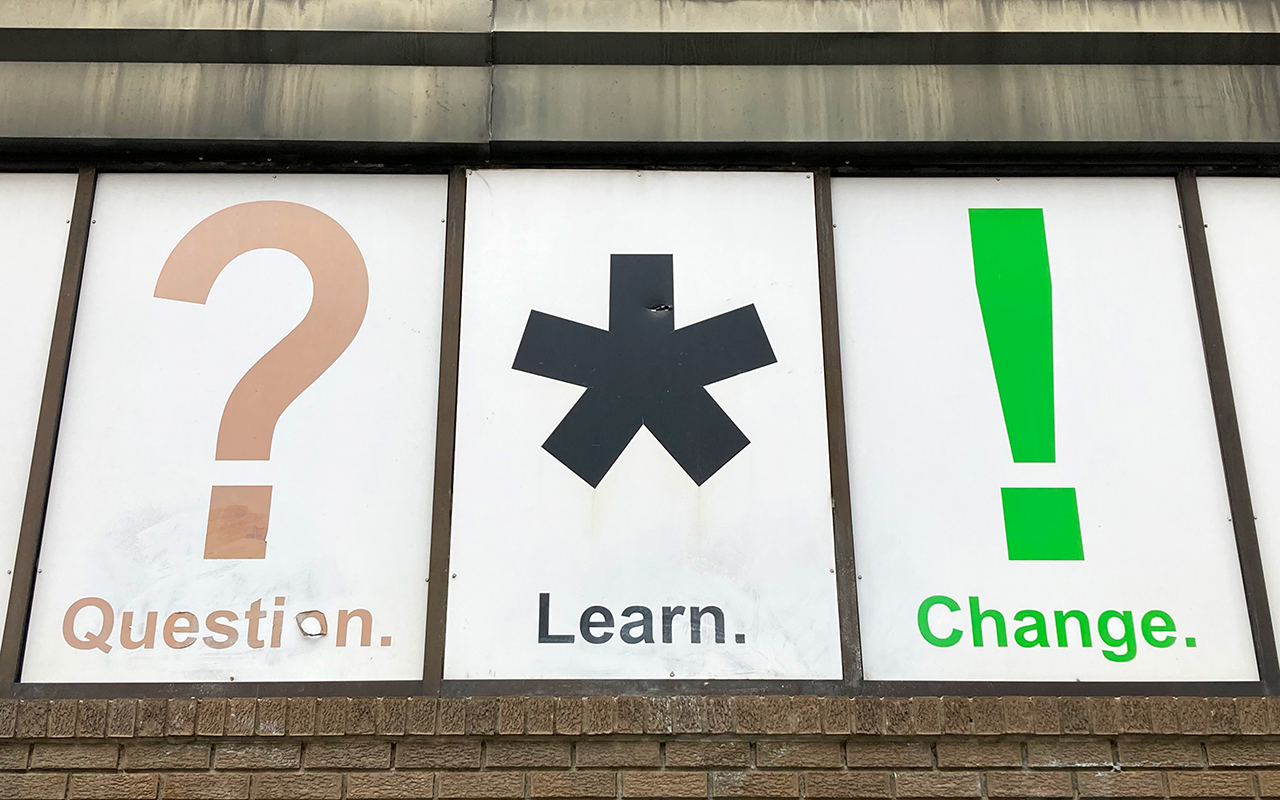

Self-government goes beyond any formal judicial settings or structures of government. It is an artform, the conducting of our own conduct. It is a practice that needs to be continuously performed and a skill that needs always to be nourished, maintained, and cultivated. “Political Culture” and education are key to governing ourselves in common. A functioning democracy is supposed to create good citizens who are capable of self-rule that goes beyond learning civics; democracy is a practice attained through knowledge (and) over time—individually and collectively. However, Alexis de Tocqueville already worried that those living in democracies forget how deeply they depend on one another (see Eliasoph, 2013, p. 13). He foreshadowed what sociologist Andreas Reckwitz calls our current Society of Singularities, a system pervaded by a self-centered NIMBYism. The most concerning aspect of this decades-long social alienation is that citizens have a hard time learning how to link themselves back together. Nowadays the question seems to be: Do people want to practice and learn these governmental skills? Do they really want to self-govern? It is an old question, but a crucial one that remains pressing. Philosopher and theologian Cornel West goes even further, asking if people truly want to be free through self-rule or if this is too much of a burden for some. To counteract such developments, diplomat and scholar Richard Haass has proposed a “Bill of Obligations: The Ten Habits of Good Citizens,” a kind of contract “between individual citizens as well as between citizens and their government.” These obligations are moral rather than legal imperatives that must be undertaken voluntarily. Political scientist and democracy advocate Danielle Allen refers to this conduct as “habits of citizenship”, affirming that a democracy can only truly thrive on the basis of its citizens’ voluntary commitment, which must go beyond legal provisions. Being governed and guided by voluntariness amounts to an ethical precept, a binding notion of self-government and a necessary rather than merely sufficient condition for democratic self-rule. One key component of self-government is the skill set needed to perform it: civic education.

Civic Education and the Quality of Democracy

A study by political scientists Kay Lehmann Schlozman, Henry E. Brady, and Sidney Verba shows that more education leads to more active participation in a society and affects the kind of citizens people become. Civic skills are needed throughout one’s life and are mostly attained through education, generating not only higher incomes, but also intensifying people’s interest in politics. It is fundamentally important that people voluntarily educate themselves, as this is the only way in which democracy can function: “wherever the people are well informed they can be trusted with their own government.” However, like all instances of voluntariness, this act too is impeded by a lack of access to the education system, economic inequality, and time constraints, which limit opportunities for self-education and self-government. These constraining circumstances are particularly tragic: the “Father of American Education,” Horace Mann, a nineteenth-century educational reformer, already hailed education as “a great equalizer of the conditions of men.”

The first female associate justice of the Supreme Court, Sandra Day O’Connor, is a lifelong advocate of civic education who underscores its fundamental role in a democracy. In 2009, she founded the nonprofit educational group iCivics to provide children with a chance to learn how the government functions and to become better citizens, as “democracy is not inherited at birth but rather learned in school”. The deterioration in civic knowledge is further imperiling U.S. democracy. According to a 2017 survey, just one in four Americans can name all three branches of government and 37 percent cannot name a single right protected by the First Amendment. The civics deficit is further illustrated by the lack of teaching in the subject: just eight states and the District of Columbia require a full year of high-school civics education and less than a fifth of more than 1,000 colleges and universities require any civics coursework according to a 2015 study. Students have almost no exposure to civics: schools and universities now see it as their task to prepare young people solely for future jobs rather than equipping them to live in a democracy.

According to a study by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), only 22 percent of U.S. students are proficient in civics. Another critical issue is the amount of money spent on education and the different subjects taught. The U.S. federal government spends $50 per student per year on Stem (science, technology, engineering and math) compared to $0.50 per child on civic education, a number that has in fact increased from $0.05 in 2021 (see Civics 101, 2023). These numbers seem to be reflected in the flourishing of Palo Alto and a lackluster Washington, DC. The distribution of funds has historic roots that can be traced back to the space race. This vast discrepancy between the two fields is a problem for U.S. democracy, though it is a matter of both/and rather than either/or. Oppenheimer may not have beaten Barbie at the box office, but it surely has in the field of education. The ideal solution here would no doubt be a Barbenheimer.

The Quest for History: Teaching Civics and the End of Democracy?

The first American history war broke out in the aftermath of the American Revolution, which is hardly surprising given that John Adams himself stated: “The history of our Revolution will be one continued lie from one end to the other”. The founding of the republic led to extensive history writing, the establishment of modern public schools in the early 1800s, and the corresponding, never definitively answered question: “Who is an American?” A nation is “an imagined political community” and its “historical memory is a key to self-identity”, which is precisely what makes history and civics such a delicate topic.

The most widespread general reflections on civics as a subject and civic education throughout society can be dated to World War II and its aftermath, and subsequently to the early 1990s, when some hailed the End of History in a dual sense. The most recent “civics battle” between the 1619 and 1776 projects showed once more that the most profound challenge lies in defining what counts as civics and shared history. The states have a decisive say in education standards, and laws have recently been passed to restrict certain topics in the classroom.

Yet history must not be cancelled. We have to accept, as historian Eric Foner put it, that “[h]istory always has been and always will be regularly rewritten, in response to new questions, new information, new methodologies, and new political, social, and cultural imperatives.” In 2019, political scientist Danielle Allen and Louise Dubé, Chief Executive Officer of iCivics, led a group of educators and scholars in an attempt to negotiate a way forward across the politically polarized spectrum. Their report, Educating for American Democracy, did not offer a national curriculum of civics but instead put forward a roadmap outlining how to think, debate, and disagree, while trying to balance American pluralism with a shared national story. Meanwhile, the proposed Civics Secures Democracy Act of 2021 does not even include authorization for the Secretary of Education to prescribe a civics or history curriculum. It is, however, a sign of the increased significance of this topic and, potentially, a tentative first step in the right direction.

We are at a critical moment, one that often looks like a downward spiral of decline: in the numbers of democracies, the quality of Western democracy, self-government (by choice or as a result of poor civic education and civics), and the quality of civics. Many non-profits and initiatives by civil advocates are, however, working hard to support self-government, to create opportunities for civic responsibility, and to foster civic education. All of us are needed—informed, attentive, pro-democratic, active citizens—to create an inclusive, pluralistic, and more equal democracy. The imperative must be to act voluntarily and strive for civic education, as “[d]emocracy may not exist. But we’ll miss it when it’s gone.”

Suggested Citation: Herzan, Pia: “Committing to Civic Education Voluntarily. A Res Publica in a Liberal U.S. Democracy”, Voluntariness: History – Society – Theory, October 2023, https://www.voluntariness.org/committing-to-civic-education-voluntarily/.