Twilight Areas of Voluntariness. A Panel Discussion on the Significance of “Voluntary” Participation in Nazi Crimes

“No dictatorship can survive without voluntariness,” stated Thomas Lindenberger in concluding the speech that kicked off our panel discussion. At first glance, one might think that this only applies to academics, administrators, or military officers who are enthusiastically committed to their ideologies. Yet voluntary action is more multifarious than it appears. We also need to scrutinize the responsibility of broad segments of the population for their role in an inhumane social system in order to gain a deeper understanding of its functioning, beyond the motives characteristic of perpetrators who act out of conviction. Historians, together with researchers working on memorial sites, have long been developing new approaches to the analysis of ideologically conformist action in dictatorships that go beyond the issue of conviction. This perspective is central to our research group’s subproject on “Voluntariness and Dictatorship” and to the work of our Mercator Fellow Alexandra Oeser.

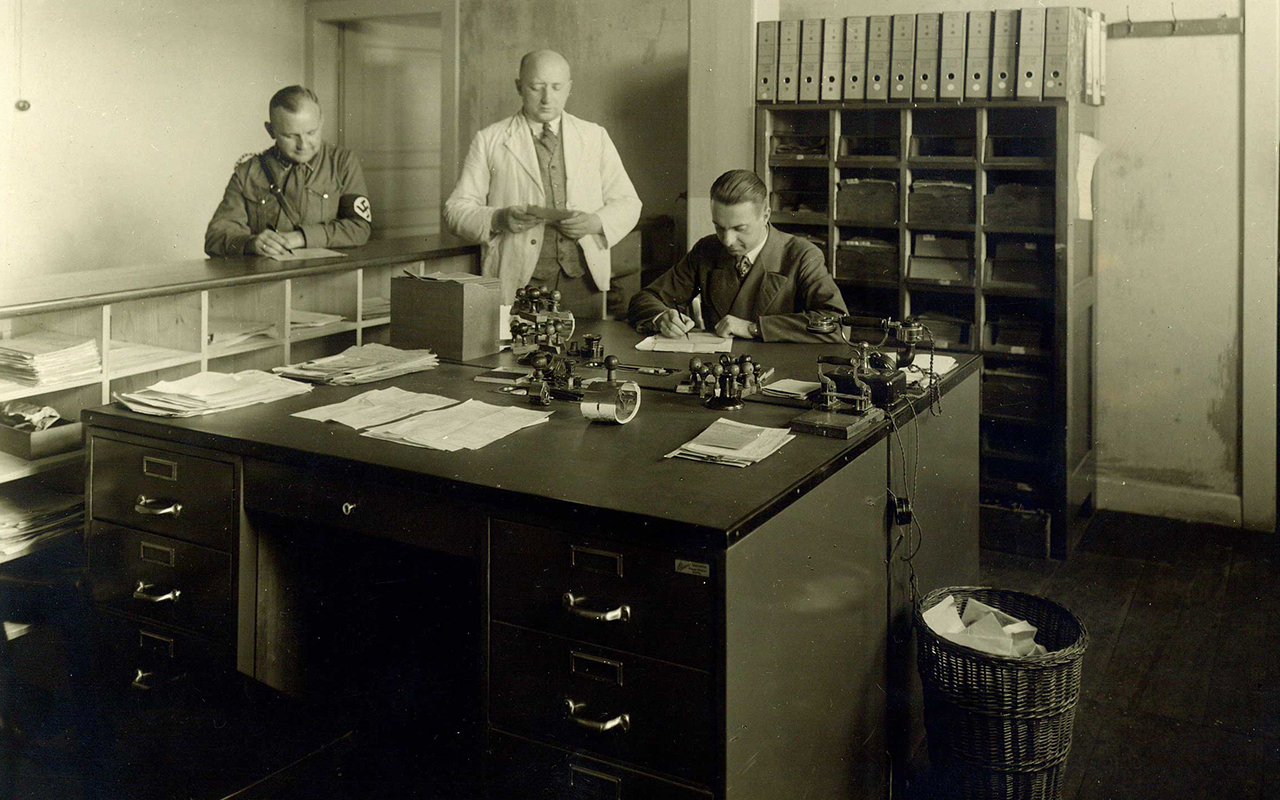

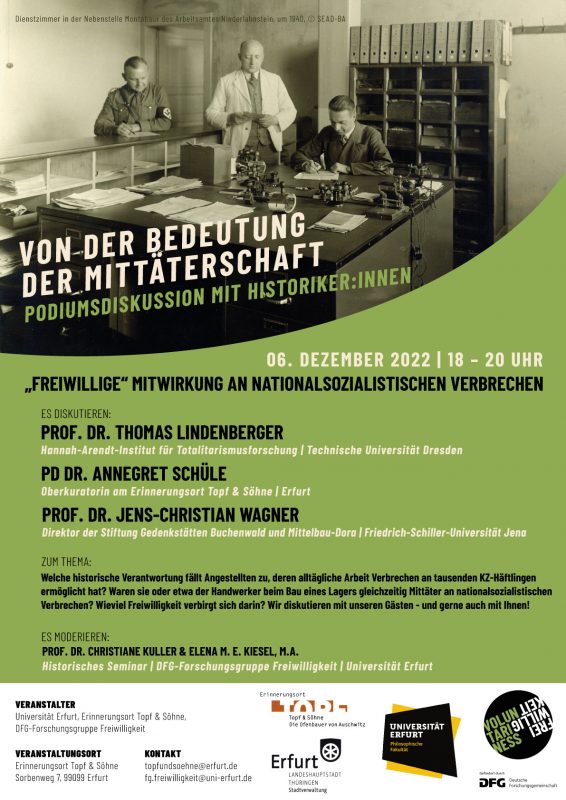

In light of this research interest in “voluntary participation in dictatorships,” the project team, made up of Christiane Kuller and Elena M. E. Kiesel, invited historians and specialists in memorial work in Thuringia to a panel discussion on December 6, 2022. Prof. Dr. Thomas Lindenberger (Hannah Arendt Institute for Research on Totalitarianism, TU Dresden), PD Dr. Annegret Schüle (Chief Curator of the Topf & Sons Place of Remembrance, Erfurt) and Prof. Dr. Jens-Christian Wagner (Director of the Buchenwald and Mittelbau-Dora Memorials Foundation, FSU Jena) engaged in a lively discussion with the research group and an Erfurt audience at the Topf & Sons Place of Remembrance. The Topf & Sons company, with its substantial workforce, built incinerators for concentration camps during the Nazi era. This site of remembrance, located on the former premises of the oven manufacturer, itself raises questions about the “voluntary” participation of “ordinary citizens” in the Holocaust. In what follows, I present a number of observations arising from this fascinating debate.

Voluntariness, Compulsory Service, and Forced Labor

In the light of a variety of contexts, it became clear over the course of the evening that voluntariness plays a system-supporting role even in dictatorial regimes. Annegret Schüle, for example, pointed out that the issue of voluntariness or participation tends to be related to the “little people.” The historical study of voluntary action thus becomes especially interesting with respect to situations that entailed the making of decisions, that is, gauging the conditions and consequences of action. To ask whether Hitler acted voluntarily, meanwhile, seems superfluous. Voluntariness cannot be reduced to ideological enthusiasm, but nor is it necessarily opposed to dictatorial coercion. Instead, much like the concept of Eigen-Sinn, it is located between the poles of participation and resistance or may involve elements of both. This in itself prompts us to ask how productive it is to probe whether action or “participation” was in fact voluntary or whether it might be more revealing to shed light on the conditions of voluntary action in any given case.

First, though, Thomas Lindenberger identified not coercion but duty (or obligation) as an important reference point of voluntariness. Historically, in bourgeois societies, voluntariness superseded compulsory service and replaced state infrastructure, as in the case of fire-fighting services. But freedom of choice and voluntariness are relevant even under conditions of obligation. As Lindenberger noted, the introduction of various forms of compulsory service under National Socialism—the Reich Labor Service in 1935 and the Service Obligation (Dienstverpflichtung) in 1943—did not necessarily meet with social opposition. In the course of the debate, the guests thus tended to identify duty and coercion as concepts that contrast antinomically with voluntariness—that is, they are opposed yet connected with it. Voluntariness and duty, in other words, do not necessarily function in binary fashion, but have in common an ethos of service to the community.

Jens-Christian Wagner also underscored the many nuances discernible in categorical reflection on a possible triad of voluntariness—duty—coercion. The diversity of individual-situational realities blurs the boundaries between free wage labor, compulsory service, and forced labor. National Socialist racial ideology also played into that, due to which (forced) labor could open (and close) very different possibilities for voluntary action. The diversity of forms taken by service obligations also opened up different spheres of action and to us it reveals very diverse historical circumstances. In retrospect, the question of “voluntariness” more than once provokes conflicts of memory: How, for example, should we classify the case of Hugo Dornhofer? Although registered for compulsory service in 1943, he had a regular employment relationship as a foreman and supervised infrastructural expansion at the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp while receiving a normal wage.

Free Wage Labor and Eigen-Sinn

Still, it seems fruitful to explore potential situations of voluntariness in the historical context of free wage labor relations under National Socialism—as in the case of the Topf & Sons workforce. In this context, however, Annegret Schüle pointed out that the participation of employees in the everyday working life of the Topf & Sons company was based on an employment contract. Those who fulfilled their work duties and participated in a criminal system were, therefore, only acting “voluntarily” to a limited extent. Yet Schüle also argued that the importance of voluntariness is thrown into particular relief against the background of the exculpation strategy pursued after 1945, as conveyed in the claim that “We had no choice.” What options for action were there? In fact, the postwar reappraisal of the Nazi past soon revealed that in some cases employees went beyond the fulfillment of their contractual obligations, working for a company even in their free time or in old age. Moreover, historical research has shown that the German oven manufacturers could choose whether to cooperate with the Nazi regime—of six companies, three did so. Those at the top of these companies and their employees, then, cooperated and supported the regime even beyond contractual obligations and coercive elements.

However, from the researcher’s perspective, it is often difficult to assess historical actors’ awareness of the effects of their cooperating or facilitative actions and thus to determine their possible complicity—as in the case of each individual employee at Topf & Sons. Within the framework of their employment contracts, actors also imbued their tasks with meaning, which is not always accessible to historical research. Here we have to consider the everyday “normality” of action within an enterprise in connection with economic or private interests if we are to at least approach actors’ perspective.

Voluntariness as an Ethical Category

Despite these nuances that emerge when we contemplate options and conditions for action, voluntariness continues to function as a powerful ethical criterion for evaluating what people do. This ethical significance presents itself even more starkly if we turn to voluntary action by victims. Here, Wagner emphasized that it would be quite wrong to ascribe voluntariness to the actions of prisoner-functionaries (Funktionshäftlinge): one’s location on either side of the perimeter fence constitutes a categorical difference. Even the action options that existed, Wagner contended, are not amenable to assessment, let alone condemnation, given the arbitrary and existentially threatening conditions of action. Yet, as the research group would argue, it is precisely with respect to these situational moments that it becomes crucial to show how voluntariness functioned as an ascription. This also takes us into the always thorny perpetrator-victim debate. Ultimately, the scholarly research emphasizes that prisoners should always be seen as subjects. Yet when it comes to voluntary action by victims, historians’ aspiration to empower actors by ascribing to them agency over voluntariness risks downplaying perpetrators’ responsibility. Here, as one member of the audience suggested, we might highlight an ethical limit to the category of voluntariness, a proposition with which our debaters engaged critically. Alexandra Oeser, for example, proposed that we make a distinction between voluntary actions by victims and those of perpetrators, while introducing the concepts of “passive” and “active” voluntariness. Others emphasized that even this distinction does not eliminate the ethical connotation of attributing voluntariness to victims.

What came to light is that questions about “voluntary” participation in Nazi crimes require a sensitive approach, especially with regard to the ethical dimension of voluntariness. In order to avoid posing as judge and jury when we consider historical actors and the extent of their participation, the key prerequisites are close scrutiny and methodological precision. It is vital to pay attention to historical-situational realities, while also taking actors seriously and granting their actions the requisite complexity. This requires us to examine voluntary action as it exists along a graduated spectrum, while scrutinizing both the conditions and consequences of decision-making. In the end, within research on voluntary participation the responsibility remains to bear in mind the ethical charge of the term. “Voluntariness” is thus a concept – maybe particularly complex, but also particularly revealing – that also points to a basic problem of historical judgement.

Suggested Citation: Katzek, Meike: “Twilight Areas of Voluntariness. A Panel Discussion on the Significance of ‘Voluntary’ Participationin Nazi Crimes”, Voluntariness: History – Society – Theory, March 2023, https://www.voluntariness.org/twilight-areas-of-voluntariness/.