Voluntary Policing vs. Police Violence: The Central Citizens’ Defence Committee in Northern Ireland

Voluntary policing by neighborhood watch organizations and vigilante groups is often associated with conservative attitudes or right-wing radicalism. These groups present their voluntary engagement as a form of self-help vital to securing “law and order” in situations of high crime that are allegedly linked with moral decay. Striving to “safeguard” their neighborhoods through patrols and surveillance activities, they concurrently exercise social control over local communities. In many instances, these voluntary policing endeavors stem from a discriminatory or racist mindset that is geared towards “others,” such as immigrant or black communities, “hippies,” homeless people, and groups of youths exhibiting “provocative” behavior.

Voluntary policing in itself is an illegal or at least dubious activity from the perspective of the state’s monopoly of violence. Nevertheless, its protagonists often believe themselves to be supporting the state by providing security. At the same time, voluntary policing can have far-reaching consequences. The death of 17-year-old African American Trayvon Martin at the hands of a neighborhood watch coordinator in Florida in 2012 led to the establishment of the global Black Lives Matter movement, which fights against racially motivated (police) violence against Black Americans and People of Color in general. A closer look at the history of private policing, however, reveals many cases of voluntary actors operating on the basis of a radical leftist political position, such as the revolutionary worker’s councils in the young Weimar Republic, the Black Panther Party in the United States in the 1960s, and autonomous feminist groups that carried out street patrols to help protect women against rape, for example in Hamburg’s Hafenstraße area in the 1980s.

In almost all instances, these groups are opposed to the police and in some situations even reject the state in its contemporary political configuration. They primarily engage in policing against police violence, which is viewed as prejudiced and specifically directed against their community, one defined in terms of race, ethnicity, religion, class, or gender. In this blog post, I examine one of these groups: the Central Citizens’ Defence Committee (CCDC), which emerged in Belfast at the beginning of the conflict in Northern Ireland (1969–1998). This case also demonstrates that voluntary policing is highly situational and related to a specific historical context.

The Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland and Police Brutality

The Northern Ireland civil rights movement developed during the 1960s when a new, educated Catholic middle class emerged that refused to accept institutional discrimination against Catholics in Northern Ireland. This politically leftist movement was separate from Irish republicanism and, though inspired by its anti-colonial struggle, took the peaceful US-American civil rights movement as its role model. Many of its members were students and young people inspired by the student movements of the “global Sixties.”

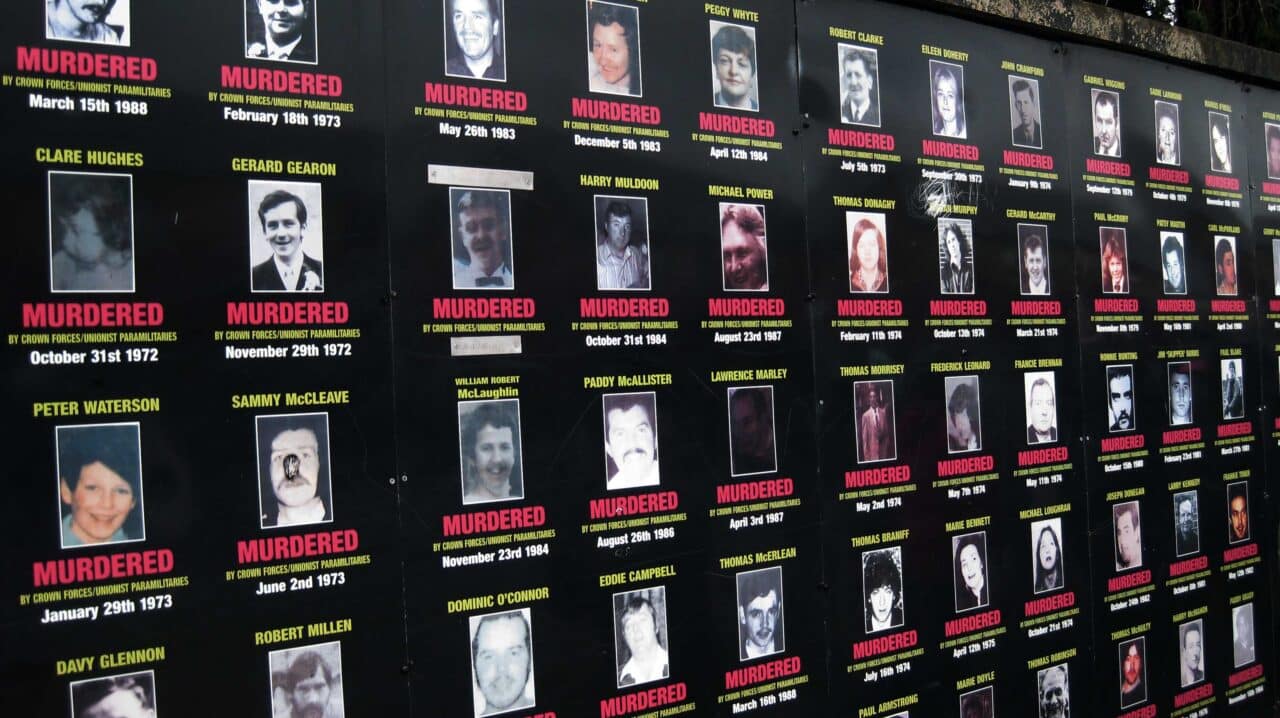

Apart from discrimination in housing, employment, and electoral representation, the movement heavily criticized prejudiced policing practices by the mainly Protestant Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and its paramilitary reserve force, the so-called “B-Specials.” This movement deployed the main tools of political expression in Northern Ireland, marching and parading, in order to campaign for its political aims, including the disarming of the police and disbandment of the B-specials. Starting in 1968, these peaceful protest marches were violently disrupted by the RUC. Police repression and brutality rapidly led to the movement’s radicalization. The situation escalated in August 1969, when violent clashes occurred between Catholic protestors on the one hand and the RUC and loyalist paramilitaries on the other, mainly in Derry (the infamous “Battle of the Bogside”) and Belfast. Many Catholic civilians were severely beaten or shot and wounded by the police.

Members of loyalist paramilitary organizations raided Catholic neighborhoods, shooting at people and burning down numerous houses, but the RUC failed to intervene. Against the background of severe poverty in the working-class areas of Belfast, these forced evictions further bolstered solidarity among Catholic residents, who immediately began to erect barricades around their neighborhoods. Organizing to protect themselves, they drew on the knowledge of older men with military or paramilitary experience, such as ex-servicemen and members of the old IRA, who had participated in earlier riots in Belfast in the 1920s and 1930s. Together with local volunteers, they began to people the barricades and organized local Citizens’ Defence Committees (CDCs) to keep out loyalists and, at least to some extent, the RUC. Here the Catholic population built upon a long history of Irish nationalist approaches to local self-organization, policing, and alternative justice.

Within the neighborhoods, residents voluntarily formed groups made up of representatives from different street sections, organizing non-violent forms of community solidarity to help those who had lost their homes, including healthcare, welfare, and education. One of these groups was the Ardoyne People’s Assembly, which was established in one of the heavily affected, primarily Catholic areas of north Belfast. Members of Ardoyne’s Protestant community had left their houses and set them on fire in a coordinated action in August 1969, thus causing a conflagration that enveloped entire streets of rowhouses, as I was informed by several historical witnesses.

The Central Citizens’ Defence Committee

The Central Citizens’ Defence Committee (CCDC) was the coordinating body for the numerous and diverse street committees that were created on an ad-hoc basis in the Catholic neighborhoods of Belfast at the very beginning of the “Troubles.” The CCDC was formed immediately after the riots in August 1969, with about 100 delegates representing approximately 75,000 local activists. The delegates included Catholic priests, persons close to Irish nationalist politicians, and IRA volunteers, members of all these groups being involved in local defense and welfare activities. Hence, the CCDC was a politically diverse, but more or less left-leaning organization. Its first chairman was Jim Sullivan, second-in-command of the Belfast Brigade of the IRA, with Paddy Devlin, a union man and Labour Party politician, as its first secretary.

In their publications, the CCDC portrayed itself as a resistance and defense organization that had emerged in response to extreme police brutality and bias against the Catholic population. Its members characterized themselves as representing the entire Catholic population of Northern Ireland, embodying all political views and ideologies. Peopling barricades and policing streets leading into Catholic neighborhoods were depicted as crucial under the circumstances. In other words, voluntary policing was portrayed as a legitimate response to police brutality and violence.

“Let it be clearly stated, and not to their credit, that the Minority in Northern Ireland did not reject the Orange/Unionist structure because of injustices; it did not reject it because of discrimination in housing or employment; it did not reject it because of manipulation in the Courts; it did not reject it because of inequalities in electoral franchise. No – the Orange/Unionist structure was rejected because of the misuse of the Police. It was rejected only when the people witnessed in their own streets or on the television screen the brutality of the Royal Ulster Constabulary. The present upheaval which has engulfed Northern Ireland started with the killing of innocent people by police guns, the burning of homes while police stood idly by or joined the arsonists, and the utter partiality of Police deployment and control when minority areas were invaded by hostile mobs.”

From “Northern Ireland: The Black Paper. The Story of the Police”

CCDC, 1973, p. 1, Northern Ireland Political Collection (NIPC), Linen Hall Library, Belfast, P1026/A, sentence bold and underlined in original

Later, voluntary policing by the CDCs and other organizations, such as the Catholic Ex-Servicemen’s Association (CESA), and the Provisional IRA, extended to activities aimed at reducing crime within local neighborhoods, particularly when these were barricaded and the RUC was not consistently prosecuting petty crime. But voluntary policing activities were mainly geared toward defending neighborhoods against Protestant paramilitary organizations and raids by the RUC or British Army. These activities also encompassed coordinated but voluntary acts of civil disobedience: members of the local community mentioned the collection and distribution of light bulbs in the streets. These were “to be installed in the front porch of each house and switched on at the same time on an agreed night. This was necessary as the army had switched off all the street lights and people were afraid to go out in the dark [the army had night-vision sights on their guns; M.A.]. Voluntary advice and labour were used so that all the houses were ready and the effect was immediate,” as Anne Tanney, one of the founding members of the Ardoyne People’s Assembly, explained to me in writing. Members of the People’s Assembly also participated in policing the entrance roads of Ardoyne so that whistles could be blown, and bin lids banged to warn of Loyalist or British Army incursions into the area.

This brief glimpse at the formation of the CCDC and its role in policing Catholic neighborhoods in the early days of the “Troubles” sheds light on one of the many facets of voluntary policing, which may include various actors from diverse political backgrounds. In particular, it highlights the fact that voluntary policing is situational, bound up with specific historical and societal conditions, though generally based on fears of real or imagined threats to one’s community. Such policing may encompass very different repertoires of voluntary action and is typically aimed at safeguarding the community by any means necessary, including violent and non-violent practices. In the case study presented here, the voluntary actors involved had a critical view of the work of the regular police and/or the state’s approach to “law and order.” Their activities were an attempt to put a stop to police practices deemed prejudiced and excessively violent. In the case of more conservative neighborhood watch organizations, situational dissatisfaction with the efficiency of the police tends to predominate. These perceptions are one of the numerous factors that induce people to engage in voluntary policing activities that they consider both justified and imperative in situations of perceived crisis. In general, the most outstanding feature of such policing is voluntary engagement, which often involves risks to the lives of the actors involved, whether in support of, in competition with, or in opposition to the official police.

Suggested Citation: Albrecht, Mara: “Voluntary Policing vs. Police Violence. The Central Citizens’ Defence Committee in Northern Ireland”, Voluntariness: History – Society – Theory, December 2023, https://www.voluntariness.org/voluntary-policing-vs-police-violence/.