Voluntary Urban Art Practices: From Caves, Graffiti & Street Art to Murals

Murals, graffiti, and public art are an ancient art form and have been part of our cultural landscape since the earliest days of humanity—one of the oldest and best-known examples being the over 30,000-year-old animal paintings in France’s Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave. A more recent rediscovery and proliferation of graffiti art, and of what is now referred to mostly as street art, took off in the 1970s in the urban neighborhoods of New York, Philadelphia, and other U.S. metropolitan regions. But Philadelphia, known as a city of many firsts, might also claim the title of the birthplace of modern graffiti, with a tradition dating back to the 1960s. At the same time, the national mural arts movement, led by Chicago’s muralists, started life as a dimension of the era’s mass political activism, portraying powerful public images in local neighborhoods, churches, schools, and union halls. This movement’s most crucial contribution was its democratic process. A new model of community art allowed ordinary people to actively participate and express themselves through artistic endeavor in their own communities, creating a new type of voluntary public art. This was a first step toward a novel urban practice that would transform shared public space and unleash the power of collective, voluntary, democratic practices.

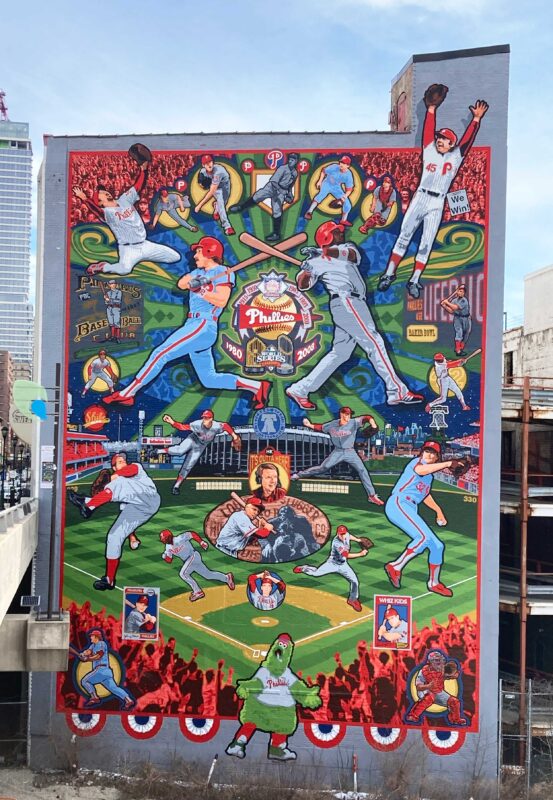

Community murals existed in Philadelphia from the early 1970s onward thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s community outreach program. But the major public impact of—and the city’s involvement in—this new art form began in the mid-1980s (see Golden, Rice, and Yan Kinney, 2002). At the same time, many U.S. urban centers had been flooded with graffiti, prompting a variety of responses from municipal politicians.

Philadelphia’s mayor Wilson Goode took office in 1984, pledging to immediately reduce the city’s “graffiti blight.” He saw this as an opportunity to empower youth by redirecting their interest to mural projects that beautified Philadelphia rather than supposedly vandalizing it. His approach led to the foundation of the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network (PAGN) and the hiring of artist and later Philadelphia Mural Arts’ executive director Jane Golden, who kicked off thecollective mural-making process in Philadelphia, nowadays known as Mural Arts Philadelphia—the nation’s largest public art program.

The Streets of Philadelphia: Mural Arts Philadelphia

Murals can be found all over the much-acclaimed “Mural Capital of the World:” on houses in diverse neighborhoods, in countless parking lots, in tunnels and on bridges, above community gardens and on the exterior walls of restaurants and department stores. This development was partly ignited by the transformation, in 1997, of PAGN’s anti-graffiti campaign into the pro-art Mural Arts Program, backed by both public and private funds. More than 4,000 works of art have been created in its 40-year history, as Mural Arts engages communities in 50 to 100 public art projects every year in its core program areas: Art Education, Community Murals, Environmental Justice, Porch Light, and Restorative Justice. The work of the now more than 50-member team goes beyond mural painting to include a floating art and ecology lab, a podcast and radio series, programs addressing arts education, and city tours.

The most important component of their work is still community involvement. Mural Arts does not impose its images and ideas upon communities, but holds community meetings to ensure that its work is based on the wishes of residents. The topics they select encompass shared events, experiences, and specific themes that resonate within the neighborhood, depicting, for example, historical scenes of significance to the community, local community leaders, tributes to specific residents, or simply beautiful landscapes that add color to the sometimes bleak surroundings (see Golden, Rice, and Yant Kinney, 2002). In many cases, these individuals’ voices go largely unheard in society or within official politics. Mural art becomes a voice for the voiceless, allowing them to be heard and seen. This is a crucial issue for a voluntarist, participatory democratic process, as“(v)oice and equality are central to democratic participation.” This urban art form is a public phenomenon to which residents gain access through their own voluntary commitment. During the process of mural painting, many residents voluntarily help by bringing food, sometimes assisting in the art process, and engaging with their community around the mural. This is an act of democracy in which everyone can participate if they voluntarily choose to. Agnes E. Mayer, U.S. journalist, philanthropist, civil rights activist, and art patron once stated that it “is this capacity of ours to work together voluntarily for the common good” that makes a functioning democracy special.

This is the beauty of the program and its voluntary dimension, which entails both beautifying walls and toppling the walls that divide people. While taking a purely aesthetic approach to fighting urban blight and sparking economic revitalization (and at times perhaps contributing to gentrification and rising rents as well), the collective mural-making process generates dialogue, builds interpersonal and social relationships, and empowers communities. Participatory public artmaking is a voluntary, collective effort in which people engage through shared agency. Residents have the choice of becoming active players rather than acted-upon, passive subjects. Their commitment within the mural-making process gives them representation and authorship of their own community. Further, their participation connects them to each other and their city as they write themselves into history. Their murals become ephemeral storytellers, Janus-faced mosaics of the impermanent history they mostly represent. Once a mural is finished, it creates an important conversation around the theme portrayed and expands the thinking of passers-by. Through this dual function, urban art ignites change and serves as an educational and social form of “positive propaganda.” This form of urban art is ephemeral, free, public and voluntary—democratic practice at its best.

The Power of Urban Art and the Civic Voluntarism Model

In 2015, some of the most prominent street artists, such as JR, Shepard Fairey, and SWOON, participated in Open Source, the largest outdoor public art exhibition in Philadelphia. JR in particular is well known for his site-specific participatory projects, which furnish a broad spectrum of people, who have been historically misrepresented or silenced, with visibility and agency. This social turn in contemporary art uses the “largest gallery of the world—the walls of the city” to free art from the artocracy of exclusive museums and to create a more inclusive democratic and voluntarist tool. Urban art in this form is an “abundance of voluntary initiative for bettering one’s own life and that of others and for turning ever higher ideals into a living reality.” Citizen participation is “at the heart of democracy,” while the participatory making of urban art amounts to a commitment to connect with others and overcome mere self-interest and the society of singularities, into which we so often withdraw.

The Civic Voluntarism Model presented by U.S. political scientists Verba, Lehman Schlozman, and Brady involves a process in which active citizens participate voluntarily, and thus without obligation or coercion, in society and politics—though I use the term “politics” in a broader Foucauldian sense than Verba, Lehman Schlozman, and Brady do. This is a form of urban citizenship, a means of directly, voluntarily, and positively impacting your own community. Here, art becomes an urban practice through which people create a city with others in a democratic, voluntary way: “Public space is the place, par excellence, for democracy: this space that belongs to all of us.” A city is a relational, performative, and shared space, which we create together through a form of voluntary urban practice. Yet this space is also an ongoing social and political negotiation, as scholars such as Lefebvre, de Certeau, Deleuze and Guattari, Miwon Kwon and Löw have set out. It is the everyday living spaces of the city, its neighborhoods, parks, and streets, that are “both the medium through which citizenship struggles take place and, frequently, that which is at stake in the struggle.”

Impermanent Monuments: Cities and Citizens

Based in Philadelphia, Monument Lab is a nonprofit public art and history study dedicated to critical conversations around monuments. In 2017, this non-profit teamed with Mural Arts and asked more than twenty of the most prolific contemporary artists working in Philadelphia and beyond: What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia? This city is a prime example of a “Concept-city” that was mapped before it was constructed, that was inhabited prior to European colonization, and that is continuing to progress with varying visions of justice and belonging. The U.S. is one nation among many that is in the midst of a reckoning over its inherited monuments. As “(h)istory begins at ground level, with footsteps”, a more inclusive, bottom-up approach to challenging history writing and monument making appears to be a good starting point. Voluntary, participatory urban art seems to be a helpful means of continuously changing ways of writing the history of cities.

Monuments, as we know them in the Western world, are statements of power and overwhelmingly portray those whose voices are heard rather than muted. In writing the history of Philadelphia, “a certain silencing”, as historian Gary Nash calls it, took place. It is time not merely to “unfreeze” monuments but to unfreeze history as well. A more nuanced dialogue about public history and art among all citizens—together with collective social practices and voluntary civic engagement—is needed if we are to pursue a more holistic approach to reimagining shared public space and life. The following two examples of projects supported by Monument Lab demonstrate an inclusive and voluntary form of civic participation through art, one that also embraces a nuanced and more complete writing of Philadelphia’s history. Civic Portal is an experimental project utilizing augmented reality to facilitate voluntary interaction. It is imagined as a tool for re-shaping the ways people respond to our inherited public art through the use of shareable platforms in cities. The world-renowned artist duo Black Quantum Futurism bring together the past, present, and future of the neighborhood of North Philadelphia to establish new or reconfigured non-linear relationships. Reclamation: Space-Times includes a monumental “Oral Futures Booth” in the shape and form of a Black Grandmother Clock. This serves as an audio recorder that collects and stores the memories and future visions of residents and passers-by. Simultaneously, the piece showcases memories of land and housing that risk erasure from public memory. These urban art approaches in Philadelphia alert us to the power of voluntary human actions in urban spaces.

“Where we stay, sit, see everything, hear everything, be everything…Philly.

Hmm…we are our own monuments. Yeah. We are our own monuments.”

(Ursula Rucker)

Suggested Citation: Herzan, Pia: “Voluntary Urban Art Practices. From Caves, Graffiti & Street Art to Murals”, Voluntariness: History – Society – Theory, February 2024, https://www.voluntariness.org/voluntary-urban-art-practices/.