Matthias Ruoss is a Swiss historian based at the Universities of Zurich and Fribourg.

War and Voluntariness: Mutter Courage Revisited

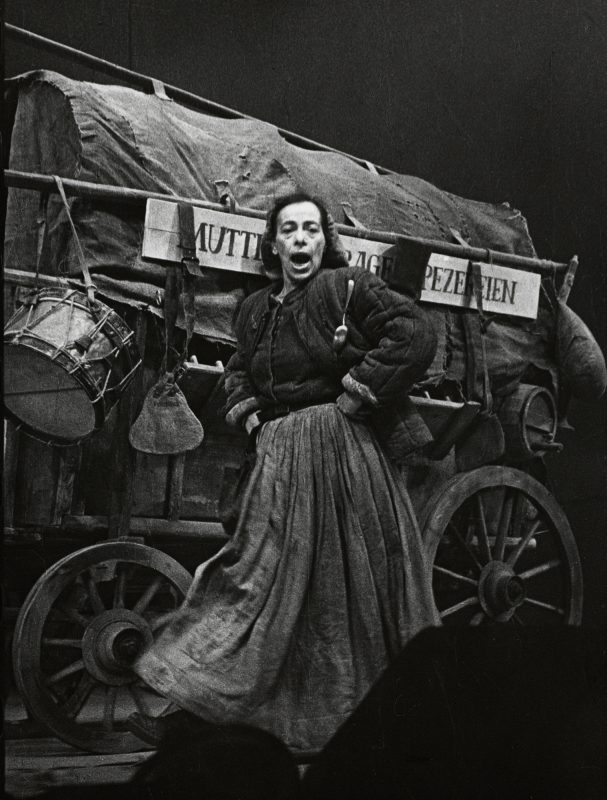

When it comes to war, Brecht helps. In particular, his play Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder, written in 1939 during his Swedish exile and premiered in 1941 at the Schauspielhaus Zurich, with its ambivalent characters, complex presentation of thorny issues and multi-layered conflicts, offers a number of aids to interpretation. To recall: the play is set during the Thirty Years’ War. It tells the story of Anna Fierling, a sutler known as Mother Courage, who tries to make a business out of war and loses her three children in the process. The action is profoundly informed by the issues of the day. Hence, the play was often understood as a warning to uninvolved individuals and neutral states not to see war as an opportunity for commerce, to profit from it, to make money out of the suffering of others. According to Brecht, however, it also entailed a fundamental, pacifist message about capitalism, war and power: “That in wartime the big profits are not made by little people. That war, which is a continuation of business by other means, makes the human virtues fatal even to their possessors. That no sacrifice is too great for the struggle against war.“ [Bertolt Brecht, Collected Plays, Vol. 5, part II, Mother Courage and Her Children, ed. by John Willett and Ralph Manheim London 1980, p. 101; via Internet Archives]

The fifth of a total of twelve scenes revolves around these “human virtues.” It takes place in a war-ravaged Bavarian village to which Courage has moved with her covered wagon. Suddenly the army chaplain rushes up to her. He has managed to get a peasant family out of their ruined farm and asks for linen to bind the wounds of the injured. But Courage gives him short shrift: „I got none. All my bandages was sold to regiment. I ain’t tearing up my officer’s shirts for that lot.“ [p. 49] At the same time, she prevents her incensed daughter Kattrin from fetching the necessary material from the wagon: „I’m giving nowt. They’ll never pay, and why, nowt to pay with.“ [p. 49] Kattrin then grabs a plank of wood and threatens her mother with it. The latter reacts with anger („You gone plain crazy? Put that plank away or I’ll paste you one, you cow.“ [p. 49]), and explains once again: „I’m giving nowt, don’t want to, got to think of meself.“ [p. 49] In the meantime, the army chaplain has entered the wagon and fetched the necessary shirts, torn them up and used them to tend to the wounded: “I’m ruined,” [p. 49] Mother Courage continues to hiss, while Kattrin is once again demonstrating her willingness to help and her compassion for the needy. When she hears a child crying in the farmhouse, which may collapse at any moment, she does not hesitate. She enters the building and rescues the infant. Her mother tries to stop her, warns her of the dangers, calls others for help, but in vain. Kattrin saves the child from certain death—only to lose her own life later in another selfless act.

What conclusions can be drawn from this imagined wartime event? With regard to voluntariness, which is what I am concerned with here, three points seem crucial to me. First, the scene makes it clear that different forms of voluntariness coexist. This is particularly evident in the helpfulness shown by the army chaplain and by Kattrin. Their commitment and assistance, however motivated, complement each other. While he tends to the wounded, she retrieves the child from the farm. Together, they ensure that the peasant family gets the help it needs. At the same time, their acts of succor conflict, which brings up a second point. When Kattrin runs into the house, the chaplain refuses to follow her („I’m not going back in there.“ [p. 49]).

Voluntariness is by no means homogeneous and of the same character. Types of voluntariness may contradict, compete with and exclude each other. Then there is a third aspect, that of renitence. This becomes apparent at the moment when Kattrin rebels against her mother. Business interests, but also motherly love, collide here with humanity and an unconditional willingness to help strangers. Kattrin is prepared to stubbornly carry through her selfless actions by force and in defiance of her mother’s authority. Generalizing these points, voluntariness can be understood as a deeply conflictual form of action. Different forms of voluntary help may be provided in concert, but they often clash, with each other as well as with the prevailing circumstances. This emphasis on frictions, resistances and conflicts, however, stands in contrast to dominant notions of voluntariness—which is often understood systemically, for which a third sector is reserved between state and market, or which is equated with social capital amenable to flexible investment. But what can a conflict-centered perspective on voluntariness do for us? What is its heuristic potential? The current war in Ukraine provides some initial clues.

Conflicting Voluntarinesses

When the Russian army attacked Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the West was shocked but also quick to help. With tremendous speed and remarkable social depth, private individuals, together with aid agencies and state authorities, responded to the disasters subsequently unleashed by the war. The voluntary assistance provided to those forced to flee Ukraine was and is particularly prodigious. Within a very short time, hundreds of thousands of people in Europe made their apartments and houses available, while others drove to the borders, picked up refugees and took them to safety. Still others remained in situ and have since contributed to the relief efforts by providing information, advice and support. The EU Council, meanwhile, moved to ensure the legality of voluntary assistance on March 4, 2022, through the introduction of temporary protective measures (including full freedom of travel; Ukrainian citizens were already permitted to travel within the Schengen area visa-free for ninety days before the war).

But no sooner had the aid got underway than cracks in voluntariness began to appear. What I have in mind here is not so much the racist violence against people of color who fled from Ukraine to Poland. In fact, these cracks run through voluntary aid for refugees itself. After just a few days, activists within the asylum movement, as well as church members, criticized the unequal treatment of refugees and the double standards that had become evident. On March 15, Pro Asyl tweeted: “And since the willingness to help is currently so great: there are also many other people who have fled wars like the one in Ukraine, from Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq for example. They too are often still dependent on our solidarity and open doors.” [Original in German] For his part, a Syrian who himself fled to Switzerland to escape war and is involved in voluntary refugee aid there stated, “I have the feeling that people are so carried away by their solidarity with Ukraine that they are forgetting everyone else who has had to flee. That hurts.” In everyday contexts, he explains, this forgetfulness is reflected in a decline in giving, including donations in kind: “Collection centers for Ukraine are overflowing with clothes. When we did a collection for refugees from other countries on Sunday, nobody showed up for hours.” Finally, a Swiss pastor reports similar feelings, even bitterness: “I know many refugee helpers who find the culture of welcome towards Ukrainians painful and scandalous.”

The Ukraine war has laid bare how forms of voluntariness overlap and differ, especially in their emphases and scope. Moreover, even if only sporadically so far, the limits to voluntariness are becoming apparent. These are conspicuous whenever initiatives and assistance come into conflict with the law. When squatters in London occupied the house of a Russian oligarch in the district of Belgravia to set up a refugee shelter, they were immediately arrested. But this occupation showed something else. Voluntariness is more than helping and civic concern: it may also articulate criticism and in this sense amount to a form of resistance. In this case, it was directed, on the one hand, against human rights violations by Putin’s government, including the bombing of Syria and discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people. On the other hand, it was aimed at long-standing tax-subsidized foreign real estate investment and the housing shortage in the English capital that has been exacerbated as a result.

These are just a few hints and indications, but they show that voluntariness is a field of tension and contestation. The lines of conflict here run between volunteers and the help they provide, but they also mark boundaries with the power relations that socially engaged activists critique and seek to overcome by emancipatory means. However, such conflicts are obscured by the normative perspectives that dominate media discourse and that inform social science research to some degree as well. One consequence of this is that voluntariness appears as a uniform and one-dimensional form of helping. Such visions may help reinforce the call to action in times of war. But they fail to capture the empirical realities.

Suggested Citation: Ruoss, Matthias: “War and Voluntariness: Mutter Courage Revisited”, Voluntariness: History – Society – Theory, May 2022, https://www.voluntariness.org/war-and-voluntariness-mutter-courage-revisited